As the commission got underway, my father, Dr. Charles T. Peterson (1913-2007), was in the process of retiring and moving from London, Ontario to Duncan, British Columbia. In fact, I believe he had already settled in Duncan when I got a telephone call from him, asking me to type out his 16-page submission, dated November 12, 1978. I was living in Timmins, Ontario at the time, so he mailed me the handwritten document, and I mailed a typed version back. He then submitted the typed one to the commission.

|

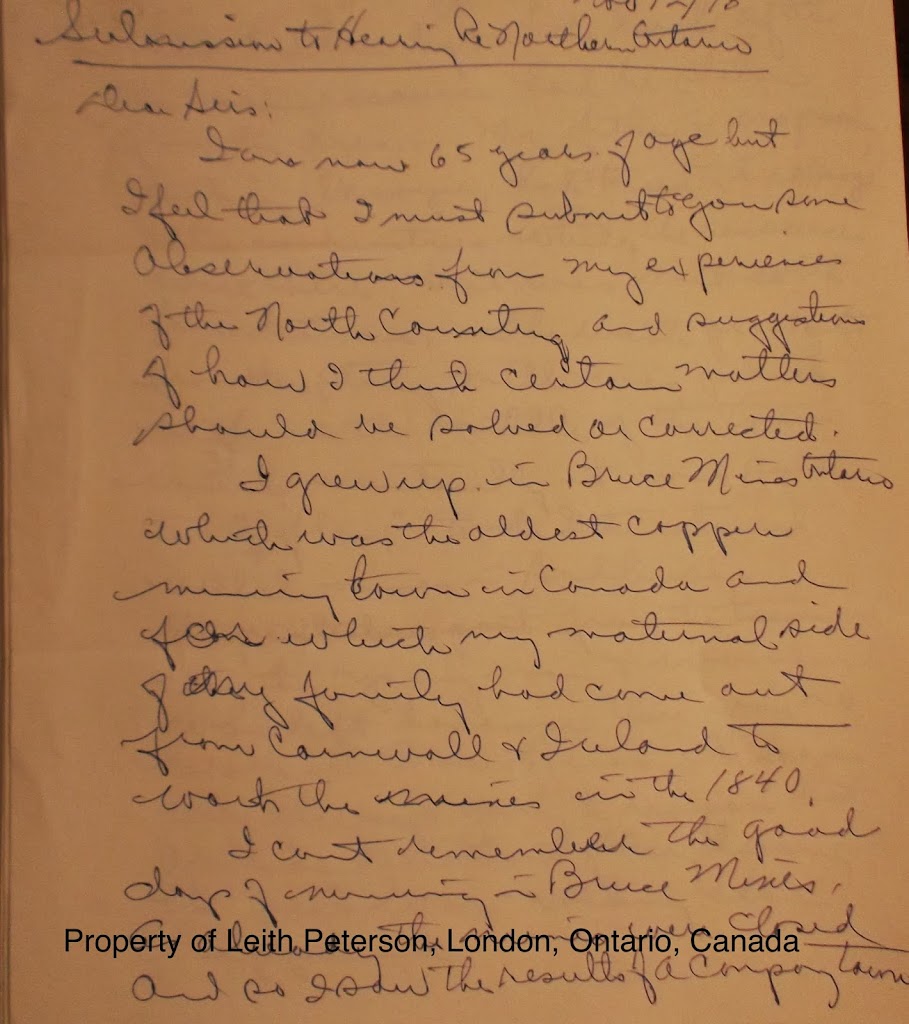

| First page of Charles T. Peterson’s RCNE submission, 1978 |

[For further information about my father, please click on the “Charles T. Peterson” label in the right sidebar.]

Although dad presented some very important views in his piece, he made, in my opinion, a number of sweeping generalizations and inflammatory accusations about various matters. This may explain why he said the commission rejected it.

Nevertheless, I think it is worth revisiting some of the content of his work because of the controversies that continue to swirl around environmental issues, not only in Northern Ontario, but throughout Canada. I say some of the content because I have edited out a number of particularly contentious sections from the original manuscript. I do not know if all his assertions, as presented below, are accurate. In addition, I suspect some of his contentions are gross generalizations or exaggerations. Please read with these caveats in mind.

|

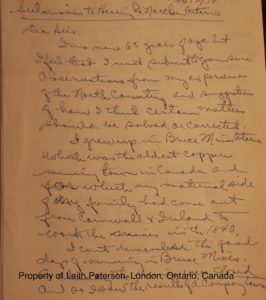

| Charles T. Peterson holding fish, ca. 1960s, location unknown |

November 12, 1978

Submission to Hearing re Northern Ontario

Dear Sirs:

I am now 65 years of age, but I feel I must submit to you some observations about my experiences in the North Country and suggest how I think certain matters should be solved or corrected.

I grew up in Bruce Mines, Ontario, which was the oldest copper-mining town in Canada, and for which the maternal side of my family had come out from Cornwall and Ireland to work the mines in the 1840s.

I can’t remember the good days of mining in Bruce Mines, as already the mines were closed, and so I saw the results of a company town that had been left in the lurch after the main resource had been [taken] from the area. My father, a progressive-thinking lawyer, had tried to encourage other industries when the resources were there, but was met with frustration. The waste products of the stamp mill, called “skimpings,” were piled high in the middle of the town until they were eventually sold as a “flux” to [a mine in another city].

The greatest export from this town were the young men and women who left because there was no work in Bruce Mines.

The mines were always going to reopen, but outside of a short flurry during the First War, nothing else happened.

My experiences during the early years [were] working at the Bruce Mines quarry (one of the last hard-rock quarries at that time), working on a survey gang for road construction and wiring houses. But, in 1929, I graduated from high school and there was no work at all. So I went to Howey Gold Mines in Red Lake, Ontario. For two years, I worked there in order to earn money to go to university. I spent two years at Red Lake firing boilers, decking the shaft head and working the crusher house.

In 1932, I attended the University of Toronto Medical School, and obtained my first year of medicine, but then had to get out because of lack of money.

In Timmins, I was fortunate enough to finally land a job underground in 1934 [at the McIntyre Mines], and spent four to five years earning money to further my education. In that area I had to switch to dentistry because it required less years than medicine.

At the McIntyre Mines when I started, there was no recognition of silicosis as an industrial disease for compensation, and the first study about this was done at the McIntyre Mines. . .

. . .In all of these situations, I never saw an effort by educators, medical people, lawyers or executives to . . .teach biological principles to provide for a more healthy community with full employment.

All of it was centred on production, that, as soon as the immediate resources of an area were dried up, the mining company just moved out and left behind the people who had given their lives to the company. . .

. . .In talking with the ordinary person in the North, I have been told that every second car belongs to a government agency. If you try to do something, you have to have 50 studies done, so that all the money is used up before any work is done. This cannot go on. . .

If they put half the PhDs to work cleaning up the Great Lakes instead of doing studies, we may accomplish some real solutions to our problems.

Our Judeo-Christian heritage has made us believe that we have jurisdiction over the universe, and history has shown that we have only destroyed it. They have even told me there is a fresh water lake under the Sahara Desert, and people have starved for years because they do not look at the world in many directions.

The Indians [aboriginal people] believe in the Great Spirit and look at the world in seven different directions. They believe they only borrow what they have to live on from nature, and the most important aspect of life is continual renewal.

|

| “I don’t need new oven mitts,” Duncan, December 23, 1995 |

More Indians lived in the 16th century around Barrie and Orillia and lived off the land than the number of people living there now. . .

. . .If two trees had been planted for every one taken down in Northern Ontario, Northern Ontario would not be in its present situation.

My suggestions for the corrections of the problems in Northern Ontario are as follows:

1. The principles of life should be taught to our children in our schools–to make use of the resources that they have on hand and to develop them to the fullest.

2. That all “experts” be sent [out of the country] and that the common sense of values be reinstated in our policies and creative natures.

3. That mineral and forestry resources should be used for the benefit of all Canadians. And particularly for the people in the immediate environment of the community that contains these resources.

4. That instead of big teaching establishments unrelated to the community, that a certain portion of the school teaching should be devoted to the development of local resources so that people can be relieved of excess taxes.

|

| Wearing genuine Cowichan sweater, Fergus, ON, 2006 |

5. That large holdings cannot be held by multinationals. . .and if a lumber company cuts timber, it must either restore the land, or the land should be held cooperatively for the other citizens that wish to develop it.

6. That forests cannot be devastated by large machinery and then left. There must be a recycling of these resources to assure a continuous supply for our children.

Unless we become aware that we must enjoy our resources and make use of them to the fullest, and provide for continuous resources for our children and our children’s children, we will fail. This should not be, or some other country will invade us.

|

| Wearing WW2 medals, Duncan, December 27, 1997 |

We must listen to what the Indians are saying to us. From my late wife, Jay Peterson, I learned some of the sensitivity to a very noble and fine people. Our thinking about Indians has been too much guided by Hollywood–mostly played by non-Indians. Some of the most interesting people I have met have been Indian people I have picked up hitchhiking, while I was driving my car across the country. They are trying to tell us something and we should listen. Our survival could depend on it.

Northern Ontario is a vast place. It has many resources to develop and it could give our children income and a happy life. Let us value our resources as a trust to be handed down to our children. Let’s not abuse it as we are today.

Yours truly,

Charles T. Peterson

I want to stress that I am only conveying some of my father’s views as he expressed them almost 35 years ago. His views do not necessarily represent my own, or those of my/our family, friends or associates.

|

| Charles and Leith Peterson, near Fergus, ON, 2006 |

Although I agree with him that many aboriginal people have tremendous knowledge of the environment and need to be listened to, I do not agree with his sweeping generalization that all Indians are “very noble and fine.” Yes, lots of them fit this description, but I think some of them have contributed to their own and their people’s misfortune. Fortunately, there are a growing number of aboriginals who deserve my father’s “very noble and fine” praise.

I also want to emphasize that my father was expressing his opinions about Northern Ontario up to 1978. Please do not assume that the situation is the same as it was when he wrote this. The best people to address the question of what Northern Ontario is like now are the people who currently live there.