Disclaimer: My references to the writings of other people–both Indigenous and Non-Indigenous–do not in any way imply that they share my views on this matter. In addition, the images I have included are for expositional purposes only. The people in these images may not share my views. The opinions expressed here are my own, and do not necessarily represent those of my family, friends or associates.

Note One: The title of this post includes the phrase “Indigenous people who live in Canada,” rather than “Canadian Indigenous people.” because I know there are some Aboriginals living in this country who do not consider themselves to be Canadian. I recognize that many Aboriginals have legitimate grievances that need to be addressed. However, I think they are better off to try and resolve their differences, while remaining Canadian.

Note Two: The nature photos, which I took during walks in my neighbourhood, have nothing to do with the contents of this post. I included them as a reminder of our universal connection to the natural world.

A. Introduction: Two Sides to Every Story

Since January 2017, I have been working on a multi-part counterpoise.ca series about cultural misappropriation as it relates to Indigenous people who live in Canada. The reason it is taking me so long is because I have been revisiting my late parents’ and my connection, not only to this particular topic, but also to Aboriginal issues generally. It has been an eye opener for me to review 60 years of this material.

Because it is going to take me more time to finish the multi-part series, I have, in the interim, published this abbreviated one-post version.

Before I started working on this series, I considered myself to be relatively well-versed regarding the historical reasons why Aboriginal people are sometimes exploited because of the misuse of their work or ideas. But my research has made me realize the roots of the problem are much more extensive than I had realized.

Nevertheless, I had been familiar with many aspects of the topic from an early age, mainly because my late parents got involved with Indigenous issues in 1958 when I was six. For further information about my parents connection, you can check out my December 15, 2016 leithpeterson.ca post, entitled “Part Four of Four: Tribute to Jay Peterson (1920-1976), on the 40th Anniversary of Her Passing – Her Involvement With Indigenous Issues, 1958-1976, December 15, 2016,” Go to https://www.leithpeterson.ca, and click on the “Jay Peterson” label in the right sidebar, to find it.

In addition, my September 27, 2013 leithpeterson.ca post, entitled “Charles T. Peterson (1913-2007) – His (Rejected) Submission to the Royal Commission on the Northern Environment, 1978,” includes many of my father’s views on Aboriginal issues. Go to https://www.leithpeterson.ca, and click on the “Charles T. Peterson” label in the right sidebar, to find it.

My parents instilled in me a deep appreciation for genuine Indigenous creations. We had quite a few examples in our family home, some of which I now have in mine. In addition, I have other treasures that I have purchased over the years.

My knowledge of Aboriginal matters expanded dramatically when I worked primarily in Native organizations in Southern and Northern Ontario and the Northwest Territories, from 1975 to 1987. My employment in this area included some work in the cultural field. Consequently, I have some understanding of Indigenous knowledge, and appreciate why many traditionalists object to the commodification of it.

From the 1970s onwards, I have recorded my views on Aboriginal matters in published and unpublished form. I consulted with quite a few Indigenous people about my writings until around the mid-2000s. Although I got a lot of very helpful advice from these individuals, I concluded that I was often better off to work on my own. I will have more to say about why I decided to go solo in my multi-part series.

The mid-2000s was also the period when I decided to disengage from the Indigenous “cause.” Since then I have mostly been on the outside looking in. However, I have continued to write about my experiences, because it helps me to make sense of all that happened to me.

From 1990 onward, my employment has been almost entirely in the mainstream. I am not out to make a living out of writing about my experiences with Aboriginals, but I feel my perspective needs to be taken into consideration, along with those of Indigenous people writing about their situation.

I do not agree with those who think only people from the culture in question should be able to comment. Sometimes those on the outside looking in can provide insights that those directly involved cannot publicly voice for various reasons.

In April 2011, I launched both my leithpeterson.ca and counterpoise.ca blogs. A few Aboriginals have given me positive feedback on some of my previous counterpoise.ca posts. But I did not consult with them before publishing my views.

Nevertheless, I realize it is important to be very careful what I say about this subject. That is why I spent months working on my previous counterpoise.ca posts. And, as mentioned, earlier, I have been working on the cultural misappropriation topic since January 2017. During this time, I have read hundreds of articles about the misuse of Indigenous heritage. Many were written by Aboriginal people who have been personally wounded by the loss of their culture. It was heartbreaking for me to review so many accounts of the damage this has caused.

I also looked at scores of articles by People of Colour (PoC). Quite a few acknowledged they borrowed from other cultures all the time. Their main concern was that any writing about the subject had to be done respectfully and carefully. But Indigenous discussions were frequently less nuanced and more focussed on blaming cultural loss almost entirely on colonization. Those Aboriginals who thought that the cultural misappropriation issue needed to be examined in context got relatively little attention.

So, if Aboriginals who want to consider both sides of a story often get short shrift, my prospects of having my voice heard, as a Non-Aboriginal, are even worse. In fact, many social justice advocates claim that my views are of no value because of the colour of my skin. But I disagree with this viewpoint. Indigenous issues were front and centre during a number of pivotal times in my life, including my mother’s December 1976 passing.

What I am presenting is my interpretation of my experiences. This is not the same as Non-Indigenous individuals writing fictional or non-fictional accounts about Aboriginals they have no connection to. I think it is important to make this distinction because a lot of the cultural misappropriation debates have concentrated on Non-Indigenous people writing about Indigenous people without having any background to the subject matter. This is not the case with many elements of the story I am telling.

Although I frequently understand Indigenous peoples’ cultural misappropriation concerns, there have been some instances where I think the objections have gone off the rails, into an outright censorship situation. I have a right, as a participant in an experience with an Aboriginal person, to express my opinion of what I think happened in that interaction. The Aboriginal person, of course, has the right to counter my interpretation.

I pay for both my blogs out of my own pocket. Although I am working on a book about my two generations of experience with Indigenous issues, it is still at the developmental stage and there have been no financial transactions so far in this regard.

If people do not like my views, then they can ignore them. But, because there are two sides to every story, I think my opinions should be out there for those who want to consider another perspective.

B. Terminology for Indigenous Peoples Is Multi-Layered and Multi-Faceted

In the multi-part counterpoise.ca series I am working on regarding cultural misappropriation, I include a section on terminology relating to Indigenous peoples. This is because there is quite a bit of confusion regarding why and how certain terms apply to the first inhabitants of this country. Below is an abbreviated version of what I plan to include in my multi-part series.

B.1 Canadian Federal Government’s Interpretation of Indigenous/Aboriginal Terminology

The uncertainty over terminology has been heightened by numerous changes to Indigenous policy since Prime Minster Justin Trudeau took office in November 2015. For instance, in August 2017, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) split into two departments: Indigenous Services Canada, and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. While the split is taking effect, people are directed to either the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada or the Indigenous Services Canada home pages.

On the Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada site, a December 4, 2017 entry says:

“Indigenous peoples” is a collective term for the original peoples of North America and their descendants. Often “Aboriginal peoples” is also used. The Canadian Constitution recognized three groups of Aboriginal peoples: Indians (more commonly referred to as First Nations), Inuit and Metis. These are three distinct peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

What I take this to mean is that the term “Aboriginal peoples” is defined in the Canadian Constitution and “Indigenous peoples” is not.

In a March 23, 2018 article about the University of Victoria’s Indigenous Law degree program, which starts in September 2018, there is a distinction made between “Aboriginal law” and “Indigenous law.” According to this article, when Canadian common and civil laws interact with Indigenous communities, it is called “Aboriginal law.” But when Indigenous people utilize their own self-governing oral laws, it is called “Indigenous law.”

So, even though I use the terms Indigenous and Aboriginal interchangeably throughout this post, Aboriginal has a distinct meaning in terms of the Canadian legal system.

B.1.1 Indian

As mentioned above, the Canadian Constitution recognizes the term “Indian.” This is at least partly because ‘Indian” has a legal meaning in documents, such as the Indian Act. Bob Joseph provides guidance on when Indian should and should not be used in a post he wrote for the “Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples” blog. You can find the citation for this in the bibliography at the end of this post.

The most recent edition of the online Canadian Press Stylebook recommends that the term Indian be avoided “except when it is the stated preference.” Status Indians sometimes prefer it to be used.

B.1.2 First Nations

“‘First Nations people’ include Status and Non-Status Indians.”

B.1.3 Metis

The federal government defines Metis as “one of the three recognized Aboriginal peoples in Canada, along with Indians (First Nations) and Inuit.”

As Metis Adam Gaudry explained in his “Metis” entry for the Canadian Encyclopedia, the term is “complex and contentious.” I recommend reading Gaudry’s article for further information.

B.1.4 Inuit

“Inuit are the Indigenous people of the Arctic. The word Inuit means ‘the people’ in the Inuit language. The singular for Inuit is ‘Inuk.'”

B.2 Native

When I was working in Aboriginal organizations in the 1970s and 1980s, the use of the term “Native” was common. But, in a July 2016 blog post, Bob Joseph described Native as an “outdated collective term,” although he acknowledged some groups, such as the Native Women’s Association of Canada, still use it.

B.3 How Indigenous/Aboriginal People Describe Themselves

Many Indigenous people prefer to describe themselves in their own traditional way.

C Cultural Misappropriation and Related Terminology Issues

The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature defines cultural appropriation as the “taking over of creative or artistic forms, themes or practices by one cultural group from another.” This “taking over” can be a positive or negative occurrence, depending on the circumstances.

The 2015 guidebook “Think Before You Appropriate: things to know and questions to ask in order to avoid misappropriating Indigenous cultures” navigates the reader through this issue. It was published by the Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage project (IPinCH) at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. iPinCH is a “collaboration of scholars, students, heritage professionals, community members, policy makers and Indigenous organizations across the globe.”

The guidebook notes that cultural appropriation occurs all the time, so the issue is more one of cultural misappropriation, which is a “one-sided practice where one entity benefits from another group’s culture without permission and without giving something back in return.” I think the term cultural misappropriation is far more accurate and will use it as much as possible instead.

However, I will still employ cultural appropriation if it applies in a particular context, e.g., it is used in the title of the work being cited.

D Lack of Consensus on What Cultural Misappropriation Means and When it Occurs

As explained in Part C above, cultural appropriation occurs when the process is one-sided, rather than reciprocal. Although this interpretation certainly lays out the groundwork for further dialogue, there is still debate over when the process is one way.

There are also difficulties reconciling intellectual property rights (IPRs) with many Indigenous world views. IPRs are a Western construct designed to protect literary, artistic and other works, through the use of copyright, patents, trademarks and designs legislation. There is usually a commercial, individual, “fixated,” and time-limited methodology to IPRs.

But the spiritual, variable and overlapping aspects of most Indigenous philosophies often do not mesh with IPRs. Traditional knowledge does not view heritage as a commodity that can be bought and sold, so the economic rights aspects of IPRs often conflict with this.

Another difficulty is that traditional knowledge terminology is open to varying interpretations, depending on the Indigenous group consulted. I agree with those who believe this knowledge needs to be more clearly explained. As an April 2, 2018 Globe and Mail editorial pointed out, “a strong definition would only give it more value.”

Additional specifics are also required for cultural misappropriation terminology. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, writer, Brian Fawcett, is right that more exacting vocabularies, such as those from the literary, philosophical or legal traditions, would make communicating regarding this topic more effective.

I think the more specific vocabulary should be legal, but should be developed in such a way that it respects both Indigenous and Non-Indigenous protocols. However, I believe there are times when a compromise needs to be struck between the two world views.

Michael F. Brown is the president of the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, United States. SAR supports Native American research in anthropology and related fields. Brown believes “legal protocols” are needed to “resolve knotty questions.”

The 189-member Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC) is part of the United Nations World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Since the early 2000s, the IGC has been trying to come up with a global process to protect Indigenous cultural property.

Canadian Indigenous groups, such as the Assembly of First Nations, have expressed concerns about the lack of financial support they are getting to participate in these talks. This is because many of them are hoping that the IGC can make misappropriating Indigenous culture illegal worldwide.

But it seems to me that if the IGC has not been able to make much progress after 17 years, it does not seem likely this will change much, even if funding were supplied to Canadian Indigenous groups. I believe this is because tribal systems have frequently become fragmented due to the passage of time and modernity.

I am far from an expert, but, after examining this issue for more than a year, I contend it often appears to be easier to implement cultural misappropriation compliance on a case-by-case basis, or with regards to specific items, such as visual art. Trying to come up with a global interpretation is very difficult due to the many different views in Indigenous communities. For instance, some have both elected and hereditary systems, which often have different perspectives.

This is where I think Michael F. Brown’s “legal protocols” to “resolve knotty questions” could apply. There will be some instances where the issue will be relatively straightforward, such as with a tribe that has a longstanding tradition of using a particular art style or custom. But there will be others where the cultural entity has been influenced by such a confluence of factors, that it would be difficult if not impossible to confirm a cultural misappropriation charge.

Some traditionalists maintain that the way around this problem is to decolonize and create small independent nations or sovereign entities. They believe that going back to Indigenous systems wherever possible is the best route forward. I disagree with some aspects of this. As I said in Note One at the beginning of this post, I recognize that many Indigenous people have legitimate grievances that need to be addressed. However, I think they are better off to try and resolve their differences, while remaining Canadian. Many Aboriginal people are able to function successfully in both worlds.

In addition, there is a tendency for some traditionalists to idealize pre-contact societies. They make it sound like returning to the old ways will resolve all the current dysfunction. But I maintain these societies, with their frequent inter-tribal warfare, and the disparaging treatment of women by some tribes, were often far from idyllic. It might be better, in some instances, to take the best from both worlds, and create hybridized systems, that still support Canadian sovereignty, but respect Indigenous world views. However, these systems need to include economic partnerships with the Aboriginal community, that will lead to financial sustainability.

Perhaps the four-year Indigenous Law degree, which will be starting at the University of Victoria in September 2018, may cause me to revise some of my views. This program, which is the first of its kind in the world, will combine Indigenous methodology with Canadian common law. To me, this is a form of hybridity, which could lead to a better legal framework. So possibly out of this, the best of both worlds can be achieved.

E “Necessity the Mother of Invention” in My Mother’s Baby Carrying Creations – And I Was a Factor in this “Necessity”

Before working on this cultural misappropriation series, I had assumed that my father’s circa 1970 biographical sketch, which stated that my mother became interested in the “plight of Indians” in 1958 was accurate. But now that I have had a chance to examine my mother’s files more closely, it appears she was at least aware of some Aboriginal matters before this date. This was because she invented several baby carriers, which she acknowledged were influenced by a variety of different cultures, including Indigenous.

She was an artist and an art historian who saw the creative process as a continuum throughout history that was built upon and added to by successive generations and cultures. Therefore, her inventions incorporated the ingenuity of mothers throughout the ages.

She said in a 1958 London Free Press article that “necessity was the mother of invention.” As the oldest of her four children, I know I was a factor in her “necessity.” This was because I was always taking off down the street, into the water, and so on. She decided that for her three younger children, she would be prepared.

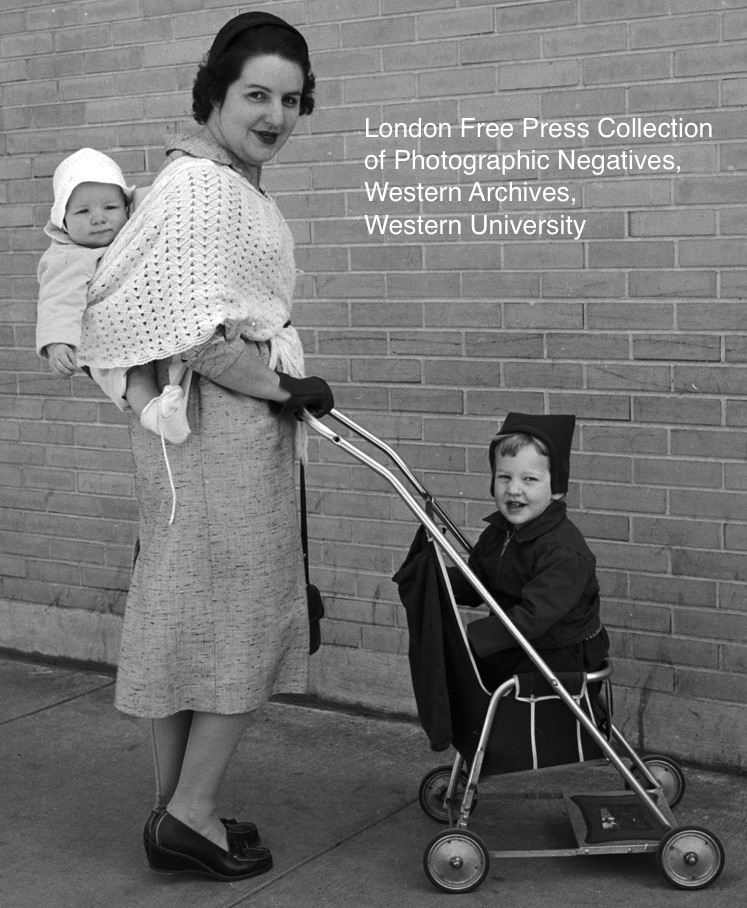

In May 1955, a photo of my baby brother Chris in a “webbing sling” on my mother’s back, with three-year old me looking on from a stroller, appeared in the London Free Press.

Since you will likely have trouble reading the cutline it says:

The Indians thought of it–Mrs. Charles Peterson adapted it–little Christopher Peterson loves it. Mrs. Peterson has three children three years old and under, and getting them from place to place presented problems until she thought of the practical solution devised by the Indians. Above she pushes three-year old Leith in her cart, while Christopher rides comfortably in a webbing sling on his mother’s back. (Photo by Ernie Lee, Free Press Staff Photographer).

This photo and cutline are part of the London Free Press Collection of Photographic Negatives, Western Archives, Western University.

Also below is a scan of the actual photo that appeared in the London Free Press in May 1955.

My mother was certainly unlike many other Non-Indigenous people in the 1950s because she acknowledged she got her sling idea from the Indians. She did not act like it was her creation alone.

(Note: Although the Peterson family home on Dufferin Avenue in London, Ontario, Canada (ca. 1951-1977) was sometimes referred to as the “United Nations,” and there were East Indians who visited our home over the years, I have concluded from looking at my mother’s files that she was crediting North American Indians for the sling concept.)

In a 1959 Chatelaine article, Mom said that she had not patented her creations “because that might lead to a business venture that would take her away from her children.” She was so selfless that she never got any financial compensation for any of her baby carrying devices. In fact, the Chatelaine article included a diagram on how to make the baby chair. The chair was initially referred to as the “Peter Perch,” and later the “babi-sitter.”

Here is a 1958 London Free Press photo of my brother Don in the “babi-sitter.”

From 1958 to 1967, the babi-sitter was one of the major fundraisers for the Service League of London. It was available for purchase in hospital gift shops across Canada, and was also sold in Switzerland, Italy, France, England, Bermuda and the United States. In 1966, the League made $3,000 on the sale of the chair alone.

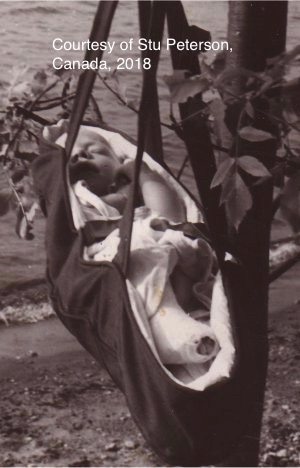

Below is a 1953 photo of my brother Stu in another one of my mother’s inventions, called the “babi-toter” (a.k.a. the “shoulder bag carrier”). The Chatelaine article also included a diagram on how to make the toter.

(Note: Stu’s legs and feet were in casts because he has club feet. His legs and feet were later straightened.)

A November 6, 1958 London Free Press article, entitled “Necessity Mother of Invention” included a photo of Mom at the stove at our home on Dufferin Avenue, with my brother Don in the babi-toter.

Joan May, the author of this article, said my mother “thought of ways Indian mothers, Eskimos and Chinese have looked after infants from ancient times. She adapted the old ideas to new ones of her own.”

I wonder if my mother was aware of the Jolly Jumper around the time that she was giving credit to the Indians for some of her baby carrying concepts. This is because Susan Olivia Poole (1889-1975) was part Ojibway (also spelled Ojibwe). She was originally from a reserve in Minnesota in the United States, and later moved to Canada.

Poole remembered how an Ojibway mother would rock her baby in a papoose hanging from a sturdy tree branch. In 1910, Poole used a cloth diaper, axe handle and steel spring to fashion her first Jolly Jumper for Joseph, the first of her seven children. She marketed her invention in 1948. In 1957, her son Joseph Poole and she patented it.

Around the mid-1960s, I remember seeing my first cousin smiling and bouncing around in a Jolly Jumper. Other family toddlers may have also enjoyed it as well, but I can only confirm that my first cousin used it.

For further information about my mother’s baby carrying devices, go to my leithpeterson.ca blog. Click on the “Jay Peterson” label in the right sidebar and look at Part One of Four and Part Two of Four of my December 15, 2016 series, entitled “Tribute to Jay Peterson (1920-1976) on the 40th Anniversary of Her Passing, December 15, 2016.”

In addition, you can read my May 4, 2012 post entitled “Jay Peterson (1920-1976).”

F. My Father Wore Genuine Cowichan Sweaters

Around 1977, my father, Charles T. Peterson (1913-2007), moved to Duncan, British Columbia, Canada. Shortly after he arrived there, he started wearing genuine Cowichan sweaters. Here is a photo of my father and me in Duncan in December 1995.

Dad continued to proudly wear the sweaters after he moved back to Ontario in 1997, right up until his final days. Below is a photo I took of him in October 2006.

Because of working on this post, I ended up doing some research into the history of genuine Cowichan sweaters. The Coast Salish, which includes the Cowichan, were expert weavers for many years before contact. By 1500, archeological records show the technique had been perfected. Blankets and other woven products were usually made from mountain goat wool, dog hair and other long fibres.

After sheep started to be raised on Vancouver Island in the 1850s, a switch was made to this type of wool. “Coast Salish European circular knitting” was first documented at the Sisters of St. Anne Roman Catholic mission in Duncan. From about 1864 to 1904, the Sisters of St. Anne provided instructions on how to knit. In the 1870s, knitting was also taught at the Anglican mission in Metlakatla.

Since the 1950s, the Coast Salish creators of the genuine sweaters have faced relentless competition from those who produce the inauthentic variety. The copies are often sold at a lower price, thereby undercutting the Indigenous sellers. As a result, the Cowichan Band Council passed a resolution, in 1981, outlining what constituted an authentic sweater. The requirements included the type of wool and designs used, and the knitting method. The band does not have copyright protection on the sweater, but registered the name “Genuine Cowichan.” Each sweater is also given a registration number and a label indicating that it is an authentic product.

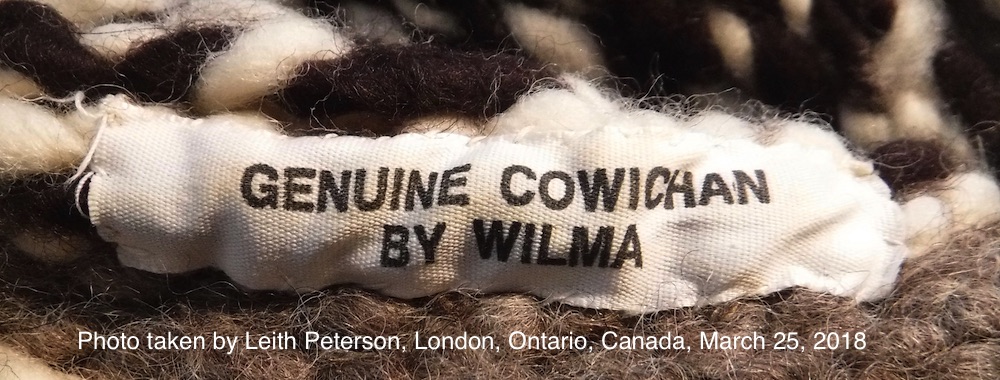

Around 1986, my father mailed me a genuine Cowichan hat from Duncan.

It has a “genuine” label in the inside.

If you have trouble reading the label, it says “Genuine Cowichan by Wilma.”

My father was very supportive of Indigenous craftspeople, just like my mother was. He often bought Indigenous-designed products for family members, including me. This was one of the ways he showed his respect for Aboriginal people.

G Conclusion

In 1991, Hartmut Lutz published Contemporary Challenges: Conversations With Canadian Native Authors. In the preface to the book, Lutz concluded that many Natives wanted Non-Native people “. . .to use self-restraint. . .to learn and listen to First Nations people before writing about them, to at least seek permission before telling their stories.”

Well, I have had numerous conversations with Indigenous people over the past 50 years. In addition, I have read many books by Native authors. My attendance at plays and presentations by Aboriginals has taught me a lot. Consequently, I think it is time to move from the back seat to the front and contribute to the discussion.

I do understand the need to get permission for the use of tribal-specific information, such as artistic designs. I acknowledge that many Aboriginal peoples’ histories and cultures have been distorted and exploited over time. In addition, I recognize that many have taken advantage of Indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge, without giving back anything in return.

Nevertheless, I think the permission aspect can end up being a form of censorship if it only amounts to silencing a Non-Aboriginal who wants to state a point of view that does not adhere to the “Aboriginals are always right and Non-Aboriginals are always wrong” narrative.

I contend there are grey areas where stopping misappropriation outright would be difficult if not impossible. In other words, I think there should be a selective application of cultural misappropriation.

I also believe the personal experiences of Non-Aboriginals who have been involved with the Indigenous situation for one reason or another, need to be taken into account. I heartily disagree with those who say that only Indigenous people can write their perspectives on this. Why shouldn’t a researcher be able to look at both sides of the story? The researcher might end up rejecting the Non-Indigenous viewpoint, but it should be available for consideration.

My view is that the ability to operate on two or more cultural paths is a healthier way to live, than to insist on only following one route. I recognize that because Indigenous people lost so much of their culture over the years, they would want to regain the knowledge and the connection. But I think it is a mistake to believe that one has to disparage one culture in order to function in another.

I will have more to say about all this in my multi-part series.

Bibliography

Academic Entrepreneur (2016, March 26). Susan Olivia Poole: An Iconic Woman for the Bank of Canada’s new Banknote. academientrepreneur.com

Atkinson, N. (2017, January 3). Knit wit: 5 things you didn’t know about Canada’s beloved Cowichan sweater. globeandmail.com

Austin (2017, August 17). Protecting Indigenous Cultural Property: Is Intellectual Property Law Actually the Answer? pacficpeoplespartnership.org

Bird, H. (2017, June 13). Cultural appropriation: make it illegal worldwide, Indigenous advocates say. cbc.ca

Bird, H. (2017, June 17). Money now available to cover Indigenous groups’ travel costs to UN negotiations. cbc.ca

Brown, Michael F. (2017). About/Upriver Home. michaelfbrown.net/about

Brown, Michael F. (2017, June 17). Beyond hoop earrings: The damaging impact of the cultural appropriation meme. michaelfbrown.net/category/culturalappropriation

Canadian Press (2018). Canadian Press Stylebook: Online guide for writing and editing. thecanadianpress.com

Davis, A. A. (2018, March 23). University of Victoria law degree a world first. macleans.ca

Face of Native (2015, March 25). For your information: History of Cowichan knitting. faceofnative.ca

Fawcett, B. (2017, June 29). Cultural Appropriation, Misappropriation and Cultural Exchange: a primer. dooneyscafe.com

Gaudry, A. (2016, November 16). Metis. Canadian Encyclopedia. canadianencyclopedia.com

Globe and Mail (2018, April 2). Globe editorial: Ottawa pits ‘traditional knowledge’ against ‘science,’ and then walks away. globeandmail.com

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2017, December 4). First Nations. aadnc-aandc.gc.ca

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2017, December 4). Indigenous peoples and communities. aadnc-aandc.gc.ca

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2017, December 4). Metis. aadnc-aandc.gc.ca

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (2018, March 22). Inuit. aadnc-aandc.gc.ca

Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage Project (2015). Think Before You Appropriate. sfu.ca/ipinch

Jolly Jumper (n.d.). History. Retrieved June 7, 2017 from Jolly Jumper. http://216.95.206.43/history

Joseph, B. (2016, July 20). Indigenous Peoples Terminology: Guidelines for Usage. Working Effective With Indigenous Peoples. ictinc.ca/blog

Joseph, B. (2017, August 15). Tips for Purchasing Authentic Indigenous Art. Working Effectively With Indigenous Peoples. ictinc.ca/blog

Lloyd, A. (2017, June 19). It’s Cultural Appropriation All the Way Down. The Weekly Standard. the weeklystandard.com

London Free Press (1955, May). New Look – Old Custom.

Lutz, H. (1991). Contemporary Challenges: Conversations With Canadian Native Authors. Saskatoon: Fifth House.

May, J. (1958, November 6). Necessity Mother of Invention. London Free Press.

McColl, K. (1959, May). Babies are meant to be near you. Chatelaine, pp. 108-109.

Meikle, M. (1987). Cowichan Indian Knitting. UBC Library Open Collection. https://open.library.ubc.ca

Ogumamanam, C. (2017, June 28). Rethinking copyright for Indigenous creative works. Policy Options. policyoptions.org

Oxford Reference (2017, February 20). Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature. oxfordreference.com

Peterson, L. (2003, May 10). Remembering Mom. London Free Press, p. F3.

Peterson, L. (2006, May 27). From party panache to practical. London Free Press, p. F3.

Stopp, M. P. (2012, Fall). The Coast Salish Knitters and the Cowichan Sweater: An Event of National Historical Significance. Material Culture Review. https://journals.lib.unb.ca

Woodrow, A. (2018, March 7). University of Victoria offers first combined Indigenous law degree. Canadian Lawyer Magazine. canadianlawyermag.com